Reflections on Juneteenth: A Personal Journey

As Juneteenth approaches, I find myself reflecting deeply on its significance, touching the particles of history that surround this consequential day, represented as a longstanding jubilation in many communities. For many, Juneteenth signifies a pivotal moment in the history of the United States that deserves to be discussed, remembered, and the many stories deserve to be told.

Juneteenth is not just a celebration; it’s a reminder of the struggles faced by so many, the ongoing fight for equality, and the importance of recognizing our shared history.

Growing up, I had no idea what Juneteenth was: no one in my life talked about it, I wasn’t taught about it in school, and I am confident that growing up in Maine, many people just didn’t know about Juneteenth. Juneteenth just didn’t exist for me. Even when I first encountered Juneteenth well into my college years, it was just a flat one-dimensional term that didn’t resonate with me until much later in life.1

I read Ralph Ellison’s posthumously published book, Juneteenth, which opened my eyes to the complexities of the celebration of the day in our history, June 19, 1866, and the forces that led up to that day. Juneteenth is an annual celebration that honors the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States, following the Union Army's victory in the Civil War. However, when I read Ralph Ellison's Juneteenth, I felt as though I had stepped into a conversation that was already ongoing, where participants didn’t take the time to explain what was happening to me. The characters in Juneteenth were on their own quest and invited me, the reader, to quietly witness what they needed to say, and anything unknown to me, anything left unsaid, well, that was now my own journey to explore.

bell hooks often speaks of the "particles of history," and that is precisely what Juneteenth represents to me: a multitude of experiences, emotions, and expressions that, across time, have gathered stories with depth of meaning and roots constantly growing into a current context. To me, that creates the constant invitation to read Juneteenth, and not just Ellison’s Juneteenth, but an invitation to explore all of the particles of this particular moment in history; to learn and continue to learn more.

I offer an invitation to explore one connected particle of history, together.

Juneteenth is the celebration of the date, June 19, 1866,2 when the last enslaved people in Galveston, TX, who were kept in chattel bondage by their captors, were freed. The Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, when Confederate Robert E. Lee surrendered himself and his troops to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. In 1862, Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people in slave holding states that had succeeded from the Union as a tactic of war by Abraham Lincoln, and with the ending of the Civil War, the many other enslaved people in neutral and northern states were unlocked from slavery when the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865.

The fear and turmoil surrounding emancipation in secessionist states can't be understated. Building to that moment, for generations before, rich white landowners lived in constant anxiety about losing the control they had over enslaved people. I encourage you to read Of Blood and Sweat: The Making of White Power and Wealth by Clyde W. Ford who chronicles the various ways slavery was an immediate part of creating the United States.3

All of this: the creation of chattel slavery, Native American slaughter and cultural destruction, the Civil War, emancipation, Reconstruction, Jim Crow and the creation of laws today that police certain groups as “bad” and protects other groups as “good,” and so much more is the context of the making of the United States, and the context of the jubilation experienced by those last emancipated individuals when they were told they were free from of bondage.

I often think about the profound moment of freedom that people experienced—my ancestors. (And I do not find myself thinking as much about the fear of those who enslaved millions of people, also my ancestors, because I don’t have to. Their legacy, their stories, are all around us to this day on the names of schools, highways, and military bases. And I like to think about my white ancestors, who I hope, were among the abolitionists I admire.) In Toni Morrison's Beloved, there’s a poignant scene where Baby Suggs grapples with the concept of freedom, a thing she has never had, so therefore struggles to understand the shape of it, the feel of it. She wonders why her loved ones are fighting so hard for her liberation, reflecting a deep confusion about the price of freedom when life has been filled with unimaginable pain. This struggle is not merely about physical liberation; it’s about understanding one’s own worth, purpose, and identity in a world that has long rejected you as a human being and long used you as a means to someone else’s end and profit.

In my studies, I find myself drawn to figures like Rebecca Crumpler, the first African American woman to become a medical doctor in the United States during the exact moment of the 13th Amendment ratification, emancipation. Her commitment to helping those in need, despite facing overwhelming obstacles, speaks volumes about resilience and duty. Crumpler, born “free,” exemplified unwavering dedication and belief in a better future that was taking shape for Black people in a way the nation had never seen. It’s hard to fathom the depth of her courage, especially in a time that continually disregarded the lives of Black people and women, and built policies to disregard, subjugate, and monitor Black people.

As I reflect on the historical realities, I feel a mix of sorrow and admiration.

I encourage you to take the time to honor those who fought for freedom and join me in working towards a future where every person is given the respect and dignity they deserve.

This Juneteenth, let’s celebrate liberty and also remember the journey that brought us all here. The past is filled with lessons and stories that deserve to be told and understood. Let's engage with those narratives—our collective history—and continue the work of justice and liberation for all.

For your bookshelf to widen your aperture of knowledge:

Juneteenth by Ralph Ellison

The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon

Of Blood and Sweat: The Making of White Wealth and Power by Clyde W. Ford

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Native Son by Richard Wright

* Bonus - a website page to peruse: Visit Galveston - And Still We Rise

For your playlist:

FRN’s Juneteenth Spotify playlist

Marian Anderson on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, “My Country Tis of Thee”

I do believe you cannot learn EVERYTHING in school. That is why having a student-minded approach to life is important.

Representation matters. I solidly grew up in a place that was white dominant, white thinking, with a white perspective. For example, we learned about Native Americans as a Native American section of history, not as an inclusive part of our history, in every step of what we learned.

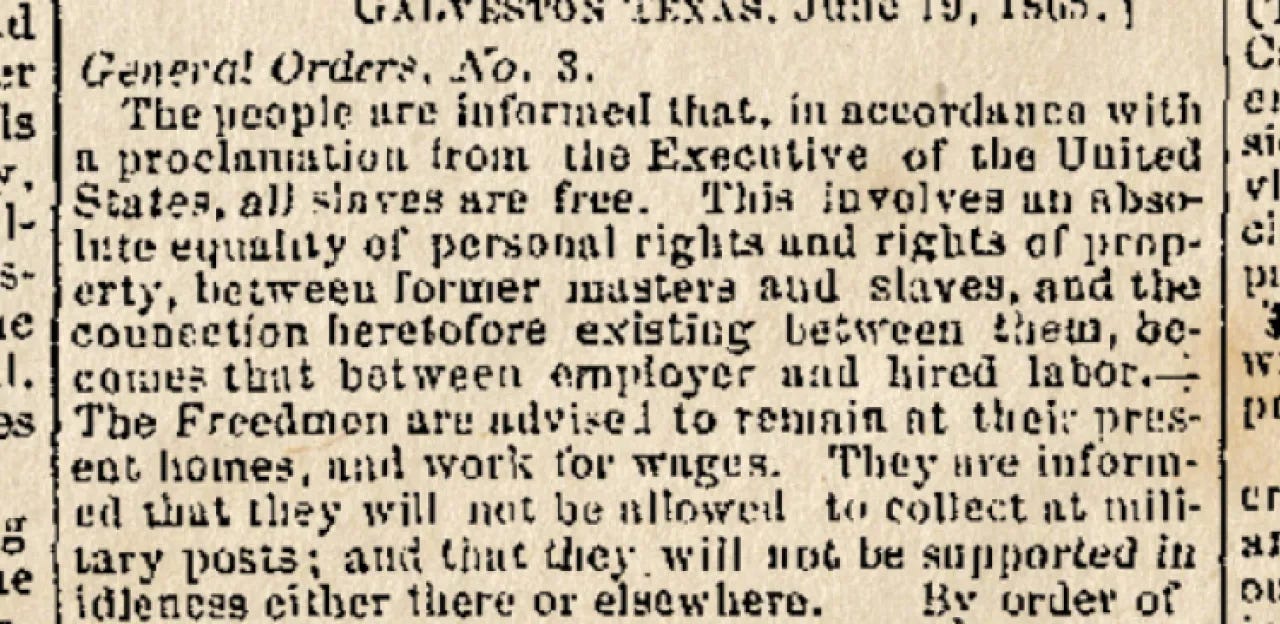

"General Order No. 3

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

Ford chronicles the laws of early colonizers to maintain bondage of Black people who were gaining their freedom by “using the master’s tools,” including dismissing the long held understanding that a Christian could not enslave another Christian because many enslaved people were from the Christian dominant country of Angola, or in 1662, to ensure enslaved babies born to white fathers couldn’t sue for freedom, the status of enslaved people would be determined by the status of the mother, a law that produced the brutal tactic of creating “breeding farms” well established even before the the end of the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1867 (which continued even after the law was passed that no new enslaved people could be brought from the continent of Africa.) The thinking was depraved and so brutal and all for the pursuit of land, money, and power. The moment was so horrific, the day-to-day so traumatic, that the white people who maintained their brutal power also suffered. Frantz Fanon writes about the connectivity of the trauma of the traumatizer to the victim in his book The Wretched of the Earth. To escape the brutality of their deeds, instead of joining the voices of the many who wanted to end slavery, those in power enacted minstrel shows and other forms of dehumanization to suppress the very humanity of those they enslaved, to make it easier to continue to dehumanize those enslaved. And these shows, the creation of the mammy character or the jovial house slave, all stem from a deep-seated fear of revolt and retribution. This fear is palpable in history and continues to fuel a complex understanding of what emancipation truly means: many do not like the term emancipation and instead believe those formerly enslaved took their own freedom for example, or for some who have not been steeped in a history that includes more voices than the dominant perspective believe that those who were kidnapped from their homes and forced to work land by brutal captors benefitted from the experience.